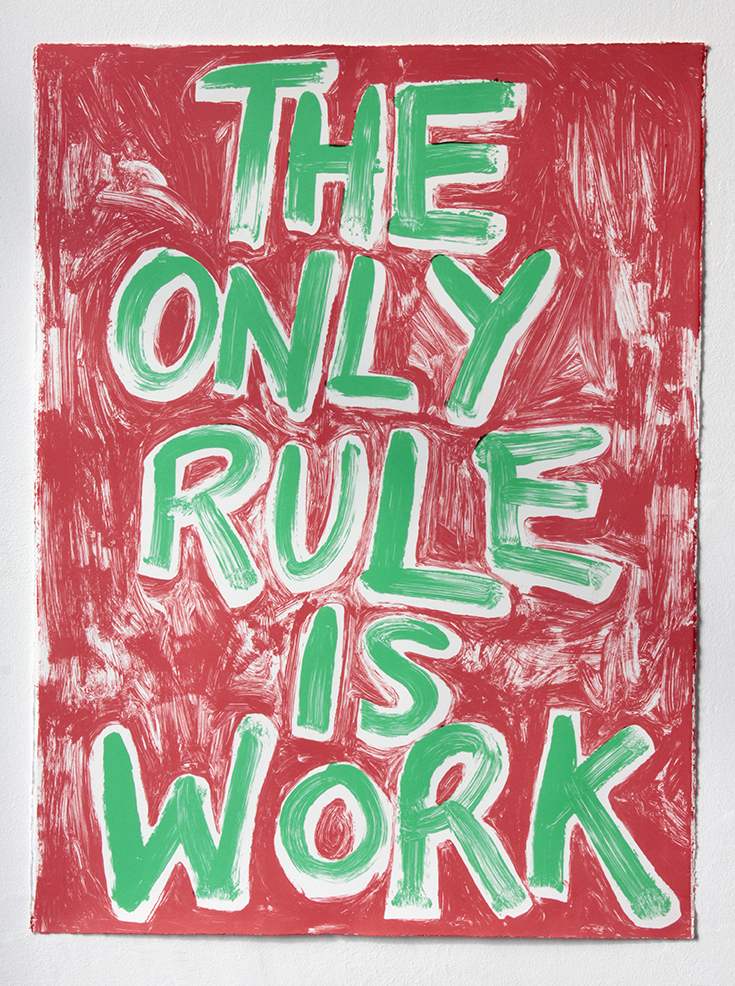

“The Only Rule is Work”

by Jen Kennedy

Commissioned for Free Hot Mess, published by Agnes Etherington Art Centre, 2022.

This Week’s Rules: Work, 2011

Commissioned by Hamburg Kunstverein

Photo: Ciara Phillips

“The only rule is work.” This bold statement by American artist and educator Corita Kent functions as “both a polemic and a question” in Ciara Phillips’ printmaking practice.1 It formed the seventh rule of the Department of Art at Immaculate Heart College (IHC) in Los Angeles where Sister Corita Kent taught from 1947 to 1968. From a contemporary perspective, the edict reads ambiguously: it focuses attention on an anti-capitalist, utopian conception of art as process at the same time that it brings to mind the actual, often-onerous, economic contexts in which this process takes place. On the one hand, “the only rule is work” is a claim for the significance of the act of making over the thing being made, an emphasis that reflects the conceptual turn in Western art during the years that Kent was teaching at IHC.2 On the other hand, it describes the imperative to work, in any place, at any time, for any fee or at any cost; the current situation in which many arts workers find themselves despite the fact that accelerated changes in the nature and condition of labour over the past decades have refocused attention on, and renewed debate about, the job of being an artist as a deeply political and tenuous one.3 Without collapsing important distinctions (and outright contradictions) between these two facets of artistic labour, Phillips’ own work visually and conceptually holds them together. What emerges through this pairing is a formal, material and social exploration of the changing conditions of work as a physical and ideological practice to be engaged, represented, and, at times, refused. Between the social possibilities, demands and necessities of work, Phillips’ prints and print-based collaborative projects open a space of critical thinking about the relations between work and sociality, work and subjectivity, and work and history.

Take, for example, the screen-print, Corin Looking (2015). In it, a black-and-whitprint of a photograph that Phillips took of her friend Corin using an antique camera to take a picture of an object in a vitrine at the National Museum of Natural History in Paris is collaged on top of several irregular, colourful and patterned rectangles of ink. The intimacy of this portrait of a woman who appears neither posed nor concerned by the gaze of her company, indicates that the photograph likely captures a moment between friends. At the same time, Corin, who is also an artist, is pictured here working, and therefore mirroring what Phillips is doing on the other side of her own camera. Just as Corin’s old-fashioned camera is a stand-in for Phillips’ own anachronistic technology: silkscreen. The two women, two friends, are working alongside one another and independently at the same time, a form of relationality that evokes industrial modes of production where workers worked side-by-side on separate manual tasks and, in turn, the historical enmeshment between social life and labour.4

Phillips’ work frequently makes visible often unrecognised forms of labour and the unacknowledged social dimensions of the conditions in which they are performed. Over the past two hundred years, art work has cycled through periods of being recognised, and not recognised, as work as such. However, since the Great Recession of the late 2000s, art workers in Canada, the US and parts of the UK and Europe have revived efforts to assert their legitimate place in the workforce and to secure for themselves the basic rights that organised labour has struggled for over a century to claim for all workers: regulated, living wages and humane working conditions. Following in the footsteps of the Canadian Artists’ Representation/Le Front des artistes canadiens (CARFAC) and the Art Workers Coalition (AWC) – respectively founded in 1968 and 1969 – associations like Working Artists for the Greater Economy (W.A.G.E.) have recently revitalised debates about how to organise artists around the issue of “work” when the sites, forms, value and meanings of artistic labour are not only difficult to pinpoint, but in a near constant state of flux. This indeterminacy is inscribed in Corin Looking, which layers a friendly outing and scenes of labour – both Corin’s and Phillips’ own. Art work, here, is intimately entangled with the relationships that it produces and that sustain it, the creative, human processes that imbue the work of art, the object itself, with meaning and value.

Free Hot Mess, 2016

Photo: Paul Litherland

Photo: Paul Litherland

While this portrait offers a deeply personal picture of the job of being an artist, the conjuncture of subjectivity, sociality and labour it represents also unfurls to expose the ways that work is always much more than the expropriation of human creativity and energy. Acutely aware of the contemporary economy’s exploitative and pervasive logic, and careful not to reproduce the moral capitalist’s apologia, Phillips nonetheless homes in on work as a potentially generative mode of relationality and as a potentially unproductive space. One of her ways of doing this is by mining the histories of her deliberately outmoded medium.

Phillips’ engagement with the radical histories of printmaking, specifically its feminist histories, is not, to its credit, primarily aimed at situating her practice within an artistic lineage. It is not reproductive, but repetitive. These are two very different approaches to history. Evocation and citation of the past in Phillips’ work do not function to establish continuity so much as they operate as forms of interruption. This is not to say that her work cannot be read as an act of homage, because indeed it is, but rather beyond this, repetition in Phillips’ work is a method of exploring how the possibilities of past forms might be reimagined in contemporary contexts.5

A case in point: Free Hot Mess (2016), a screen-print that hilariously reconfigures See Red Women’s Workshop’s slogan, “the freedom of the press belongs to those who control the press,” which itself appropriated journalist A.J. Liebling’s well-known aphorism, “freedom of the press is guaranteed only to those who own one.” When See Red, a feminist anti-capitalist poster collective, was founded in London, UK in 1974, it was driven by the idea that direct access to the means of print production could subvert and change mass culture for the better. At the time, screen-printing – relatively cheap, easy to learn, and reproducible – was the tool of choice for achieving this goal.6 Today, the graphic aesthetic language of silkscreen is still associated with activist art but, as a tool, printmaking has been consigned to the long list of communications technologies that, however briefly, promised to democratise mass media before being either recuperated or replaced through capitalist intervention and innovation. In Phillips’ hands, See Red’s hopeful call to arms is rearranged as a wry reflection on the contemporary media environment that, while arguably controlled by the many, has become a discombobulating cacophony of misinformation and “fake news”: a free hot mess.7

By pulling fragments out of the narrative flow of history and asking them to stand for themselves, out of joint with time, Phillips not only sidesteps nostalgia, but draws attention to the ways in which seemingly static images, tools and texts are perpetually reworked – and made to perform different work – by the various contexts in which they are positioned. Intentionally or not, she is heeding feminist photo-historian Abigail Solomon-Godeau’s advice. It is not, Solomon-Godeau argues, sufficient for an artist “to turn time and again to those aesthetic or theoretical operations that have in the past supported oppo- sitional work; in fact, such unflagging allegiances risk blind conservatism and might only – and unwittingly – render effects once radical into comfortable, consumable things and ideologies.”8 Far from simply reviving the historical possibilities of printmaking as an activist and, theoretically, subversive, democratic medium, Phillips emphasises the anachronistic qualities of this modality against the dominant logic of artistic labour in the present: the perpetual pressure to perform, to produce, and to perform and produce again.

Put another way, Phillips engages screen-printing and its histories to imagine alternatives to the contemporary pace and standards of production. As such, both the material properties of the medium and the discourses that have developed around it hold significance for her. The connections between screen-printing and feminism in North America and the UK are historical, practical and ideological: alternative print culture emerged in these places at the same time as the Feminist Movement; printmaking is relatively inexpensive and reproducible; and, for these reasons, it came to be associated with accessibility and democracy as both a medium and as a form of communication.9 Between the late-1960s and the 1980s, the prints produced by poster collectives and community printshops, such as See Red Women’s Workshop, the Chicago Women’s Graphics Collective, and Sister Corita Kent’s classes at Immaculate Heart (all of which have been cited in works by Phillips), played a critical role in creating the visual language of 1970s Feminism on local and transnational scales. However, the stakes of these projects are not only reflected in what they produced, but also in how they produced it. A number of the women-run print shops that sprang up in the 1960s and 1970s were experiments in feminist modes of production, resulting in collaborative and community-oriented projects that, while diverse in their politics, had a common commitment to openness, participation and pedagogy. The crux of these experiments was a shared belief that truly usurping mass communication required both taking control of the means of production and radically reorganising the social relations that formed around it.

Much of Phillips’ practice explores how communities take shape around work. The twin processes of making and finding one’s place within social groups formed through shared labour – processes that are inscribed in such prints as Corin Looking – are fundamental to her ongoing, collaborative projects, Poster Club and Workshop (both 2010–ongoing). Whereas Poster Club is a defined group of artists and friends who have been making and exhibiting print-based works together since 2010, Workshop differs in that the communities it engages, and thus the relationships it produces, change with each instantiation. The premise of Workshop is simple: Phillips sets up and works in a studio within the context of her exhibitions, inviting local residents and groups from the community to collaborate with her for the show’s duration. Sometimes these collaborations produce concrete objects, as in Justice for Domestic Workers Alphabet (2014), which Phillips produced with members of The Voice of Domestic Workers, a UK-based grassroots advocacy group, at The Showroom in London in 2013. Other times they do not. Both Poster Club and Workshop undermine the usual value hierarchy between process and product by slowing down the relationship between the two and figuring process not merely as a means to an end but as a meaningful locus of sociality.

Workshop (2010–ongoing), 2013

With Justice for Domestic Workers

Commissioned by The Showroom, London

Photo: Ciara Phillips

With Justice for Domestic Workers

Commissioned by The Showroom, London

Photo: Ciara Phillips

These two ongoing projects also bring to mind Sister Corita Kent’s dictum “The only rule is work,” which itself recalls the old English meaning of the word “work”: a general term for activity that was distinct from the Latin-derived “labour,” with its strong connotations of suffering and toil. Cultural theorist Raymond Williams has shown that it wasn’t until industrialisation that the work “work” began to signify paid labour.10 In Phillips’ collaborative projects, working together involves spending time doing things together and building relationships through a common identity or activity. In Poster Club, the collaboration forms around members’ identities as artists; their shared affiliation with a specific type of work. Workshop brings diverse communities together to collectively perform a specific type of work, usually printmaking; in fact, a survey of various manifestations of Workshop over time would offer an interesting perspective on how silkscreen as a medium produces a certain set of possibilities for the social relationships that form around it.

In both Poster Club and Workshop, work is figured as a site of sociality. By opening a gap between process and product, these projects expose the social and imaginary fields across which work is performed and in which the subjectivities and relationships of workers are constituted. Despite travelling internationally, each presentation of Workshop is explicitly local in its engagement with the issues, politics and social practices brought into the space by Phillips’ community collaborators. The relationships it generates through shared work are thus provisional and contextually contingent. In other words, this project does not offer a key to unalienated labour; rather it asks whether, in small-scale and situated instances, working together may generate forms of relationality and personal meaning beyond those determined and appropriated by capitalism.

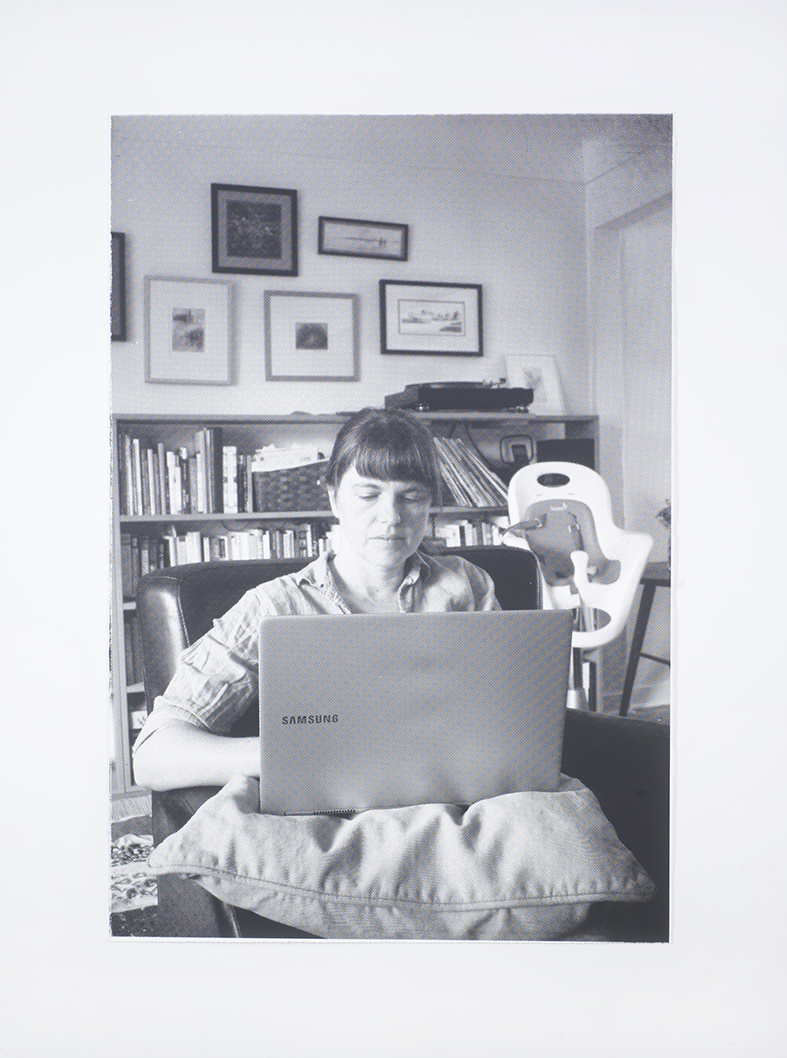

For many artists today, lack of work – especially well-paying, stable work – and inconsistent, haphazard working conditions are major culprits of hardship and alienation. These circumstances unite art workers with a larger population of the precariously underemployed and unemployed across a diverse range of economic sectors.11 What is unique about art workers, according to W.A.G.E. and others, is that outside of the cultural sphere their labour is frequently not recognised as meaningful, productive work as such, a misperception that links them to a longer history of work that has typically been performed by women. The many photographs of Phillips’ female friends working, which appear and reappear throughout her prints, illuminate this problem of recognition as it relates to both artistic and gendered labour. In Emily reading (2015), for example, a woman is pictured in a domestic space, sitting on a leather armchair with a laptop balanced on top of a pillow on her lap. A chock-full bookshelf and an empty highchair are visible behind her. The space is coded by at least two types of labour: parenting and intellectual work.12 This is not a “traditional” work site but rather a space that has historically been positioned as its opposite, the home. A far cry from the muscled masculine industrial worker who has long stood as the visual representation of class struggle, Phillips’ pictures of women artists working call to mind another lineage of feminist artists and activists who have questioned the social and economic hierarchy between productive and reproductive labour, and all that falls between.13 In 2017, the scene depicted in Emily reading is also emblematic of the contingent work and gig economy in which many artists now participate to support both their own creative work and that of others by doing the part-time administrative and teaching work necessary to sustain the cultural sector.

While frequently abbreviated to “The only rule is work,” Sister Corita Kent’s seventh commandment continues, “If you work it will lead to something. It’s the people who do all of the work all the time who eventually catch on to things.” In short: do things, keep doing things, and the rest will follow. Looking around at the frantic pace and pressure to produce that characterises artistic work today, it is easy to see how Kent’s once optimistic and open-ended promise has been appropriated by capitalism and turned into a form of cruel optimism, a productive logic wherein artists and other cultural workers are often working for and against their own interests at the same time.14 If Phillips’ polemical citation of Kent is a reinvestment in the potentiality of work, her question is: what are the conditions of possibility in which work works against, rather than for this logic? How, in the present moment, can work be imagined otherwise?

1. Ciara Phillips, artist talk at Queen’s University, 23 February 2016.

2. Phillips’ interest in Kent extends beyond this proclamation. Her reworked pop aesthetics, clever appropriation and re-direction of pre-exiting texts and the vibrant swaths and blocks of colour that punctuate her work all evoke Kent’s idiosyncratic agit-prop prints. At the same time her particular use of typography, dynamic shapes, and textile, as well as her approach to design, bring to mind other art historical precedents, notably Russian Constructivism and the Bauhaus. Just as importantly, Phillips looks to Kent’s practice as a model for experimental collaboration within artistic process and community-building. Kent’s and Phillips’ work was exhibited together in the exhibition Pull Everything Out at Spike Island, Bristol, UK in 2012. See, https://www. spikeisland.org.uk/programme/exhibitions/ corita-kent-and-ciara-phillips/.

3. See for example, Julia Aranda, Brian Kuan Wood and Anton Vidokle, eds., Are You Working Too Much: Post-Fordism, Precarity, and the Labor of Art (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2011); Airi Triisberg, Erik Krikortz and Minna Henriksson, eds., Art Workers: Material Conditions and Labour Struggles in Contemporary Art Practice, 2015, http://www.art-workers.org/index.php; and Gerald Raunig, Gene Ray and Ulf Wuggenig, eds., Critique of Creativity: Precarity, Subjectivity, and Resistance in the ‘Creative Industries’ (London: Mayfly Books, 2011).

4. The most obvious example of this way of organising labour is the assembly line, but it can also be observed in “creative” and “white collar” jobs, such as the stable system Hollywood studios use to produce screenplays and the “team work” structure of many corporate environments.

5. This concept of history is rooted in the philosophy of Giorgio Agamben. See, for example, Potentialities: Collected Essays in Philosophy, ed. and trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1999).

6. Sheila Rowbotham, et. al., See Red Women’s Workshop: Feminist Posters (London: Four Corners, 2016).

7. Free Hot Mess was produced before the 2016 US election but I would argue that its critical significance has amplified in the aftermath.

8. Abigail Solomon-Godeau cited in Johanna Burton, “Fundamental to the Image: Feminism

and Art in the 1980s,” Modern Women: Women Artists at the Museum of Modern Art, ed. Cornelia Butle and Alexandra Schwartz (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2010), 430.

9. On the history of feminist printmaking, see Jess Baines, “Experiments in Democratic Participation: Feminist Printshop Collectives,” Cultural Policy, Criticism, and Management Research 6 (Autumn 2012); 29–51.

10. Raymond Williams, Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society (New York and London: Oxford University Press, 1976), 334–337.

11. On the culture of precarity beyond the arts, see Elizabeth A. Povinelli, Economies of Abandonment: Social Belonging and Endurance in Late Liberalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011).

12. Not to suggest that parenting and intellectual work are mutually exclusive, but rather to point out that, historically, most Western cultures have ideologically (if not always materially) separated them. School closures and work from home orders issued

in response to the COVID-19 Pandemic in early 2020 (three years after this essay was initially written), have intensified discussions and debate about the relationship between productive and reproductive labour – and the spaces that have historically contained them – across North America and in many other parts of the world. The scenes of labour depicted in Phillips’ work are arguably even more illuminating in the context of the changes to many types of work that have been forced by the global pandemic.

13. See, for example, the work of Mary Kelly, Merle Laderman Ukeles, Chantal Ackerman, Léa Lublin, Marta Minujín, and Carrie Mae Weems, as well as the London-based collectives Women and Work and the Hackney Flashers.

14. Laurent Berlant, Cruel Optimism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011).

Emily reading, 2015