A Conversation with Ciara Philliips

by Astrid Helen Windingstad

An interview for Whatever happened to that bridge we crossed? Kunsthall Stavanger, 2019.

Astrid Helen Windingstad: I’m curious about the title of the exhibition - Whatever happened to that bridge we crossed? To me, it refers to something that was and now is gone. What is the title referring to?

Ciara Phillips: My dad said it on a long car journey - “Whatever happened to that bridge we crossed?” I started thinking about it not only in terms of looking for landmarks but also as a personal question and a question that might be applied in wider societal terms. I like titles that can refer to something quite intimate - a feeling, relationships, a dedication - but that also reflect outwards and open up thoughts about how we operate in the world. Here, Whatever happened to that bridge we crossed? will be a starting point for the conversations I´ll be having through the collaborative project Workshop (2010-). It’s a catalyst for discussion rather than a direct reflection on the artworks in the show. I’m hoping a lot of questions will come out of this one question.

AHW: You were born in Ottawa, Canada, and you are living in Glasgow, Scotland. You have education in Fine Art from both countries. Can you tell us about how you came to work with printmaking?

CP: As a student in Canada I studied painting, printmaking and sculpture. I wasn’t especially interested in printmaking - it felt narrow in terms of possibility. We learned about the tradition of editioning - reproducing the same image over and over again and it took me a while to realize that I could just use printing as a way of thinking. Images and ideas could expand and extend out, be altered, be singular. Later, I started thinking more about print’s interesting histories and how they relate to the democratization of information. I learned more about the history of feminist print collectives, and this refigured my interest in what print has made, and can make possible. At a certain point I realized that I could make prints however I wanted and that I could involve other people into the process - that made it feel exciting. And as a medium I like the level of uncertainty that comes from printing - the tools and methods often interfere with my intention, and I find that productive. Something happens that wasn’t entirely planned and then I have to reassess. The work is the product of improvisation - a back and forth live discussion with the work as it happens.

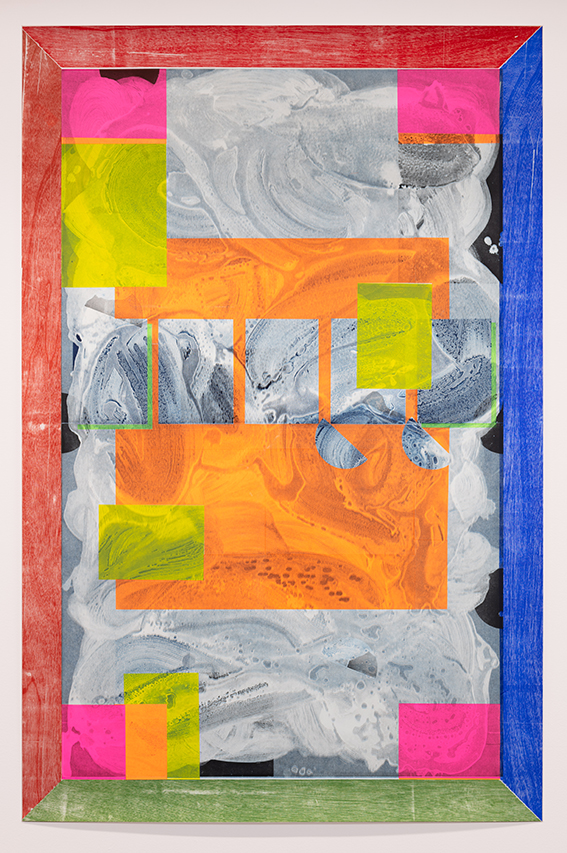

Radiate, 2019

Photo: Erik Sæter Jørgensen

CP: Yes, and then I edit a lot. But I keep the prints I am not happy with to work on again later. I like that. It creates a history within the practice that rolls over time. Things appear and reappear.

AHW: I would describe your work as diverse. Your exhibitions are often comprehensive in space, graphic in line and shape, with a variety of formats, including screen-printing, textiles, text and installation. It’s often expressive but also subtle in colour. There’s often a call for action within the projects. My first impression was that many of your projects can be seen as a demonstration through aesthetics. Can you relate to this description?

CP: A call to action is important to me. This happens in different ways, sometimes directly through text - this feels quite pointed - and sometimes through the energetic feeling of the work itself. I don’t see my works as a demonstration of aesthetics, but I do often use aesthetics to try to elicit certain feelings in the viewer.

A call to action can be created through colour for example. A direct example of this is a banner I made in collaboration with The Voice of Domestic Workers* at The Showroom in London in 2013. We used a colorful unfinished textile work of mine to make a banner saying “No to Slavery” - one of their key slogans. For several years it was used in their campaigning work and they wrote to me shortly after we made it to say that they often had their photo taken at rallies and protests because theirs was the most brightly coloured banner.

But I’m also interested in how colour can affect in less tangible ways too. How it makes you feel and what kinds of thoughts and associations it can produce. It’s not always about action though, it’s also important to create a space for reflection.

AHW: For the project Workshop, you invite various individuals and communities to work with you through print. In Stavanger, you are inviting people to collaborate with you at Kunsthall Stavanger and Tou Trykk, for two months while the exhibition is up. Will the works that are created at the sessions become part of the exhibition at the Kunsthall?

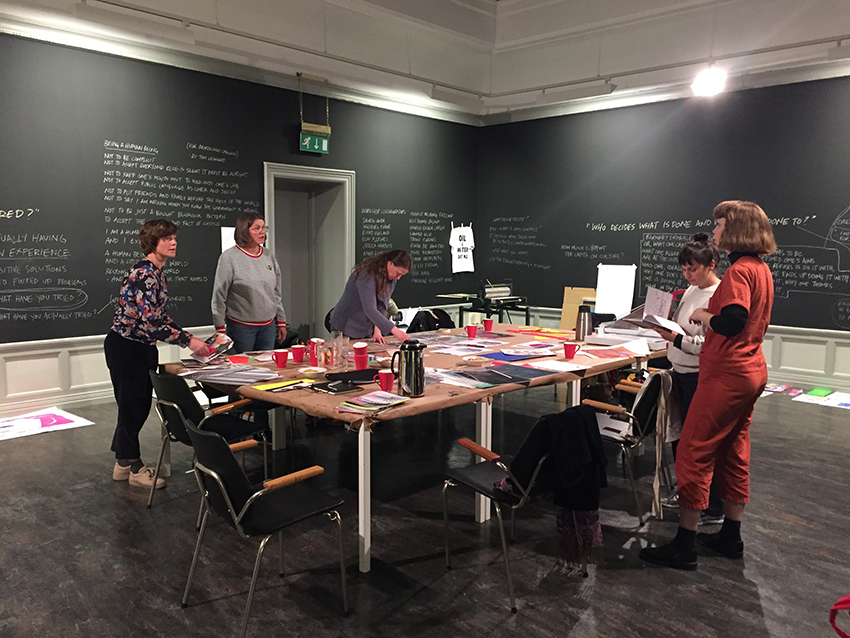

Workshop at Kunsthall Stavanger, 2019

Photos: Ciara Phillips

Photos: Ciara Phillips

CP: If my collaborators agree. Works developed through Workshop are the product of many people and so it’s not possible to say at this point what the things we make will be or how they should be presented. But there will be an accumulating of information taking place within the gallery here at the Kunsthall. I always keep a note of what’s being discussed in collaborative situations and some of those notes will gradually be added to the walls of the gallery as the project progresses. The note-taking helps me to remember what has been said and it also lets others have access to what’s being talked about and what’s informing the collaboration.

AHW: Who is participating in this iteration of Workshop?

CP: I’ll be working with two of the groups of artists, and a third group which is open for anyone. There’s also some flexibility in terms of including others as the show progresses. Typically, what happens is that when the show opens, the word spreads and people ask to get involved. What Workshop isn’t though is a drop-in session for anyone to just try their hand at printing. This project is much more about developing collaborative relationships over time than it is about a quick facilitation.

AHW: Which formats and techniques have been used for the works in the exhibition at Kunsthall Stavanger?

CP: Etching, screen-printing, and relief printing from wood and other materials, such as tape and plastic. And I’m exhibiting some clothes that I’ve made - a group of garments made in California in 2016 and a few pieces that I made in Bergen last year. For all of the large works on paper I worked primarily with master printer David Stordahl at Trykkeriet in Bergen. During our last week of working together, I asked him if we could use a large piece of cotton to clean up all of the plates at the end of each day. The work Rag - which is hanging in the Kunsthall’s foyer - is an impression of that, a record of a week´s worth of cleaning. I think of it as a full stop, an end point to the other works but also a beautiful thing in its own right. This isn’t really about celebrating the unseen, it’s more about recognizing a moment when it happens.

AHW: Texts about your work often mention Corita Kent as a source of inspiration. Kent was an artist working in the 1960s, with an experimental approach to artmaking and education. Her work circles around concerns about poverty, war and racism. Your printing practice is political in many ways. Which are your main concerns?

CP: I care about women’s rights and representation - about what opportunities are afforded to women and what opportunities are not. I think it goes without saying that we still have a lot of work to do in this area and in a sense the exhibition title is a question about that. I think we still have to fight for those bridges that perhaps we thought we had already crossed.

AHW: You often use text in your work. Is the use of text the most political part of your practice, or do you see your practice as a whole as the main political dimension?

CP: The totality of any practice is the most political part of it - thinking about what a person does with their time, who they do it with, what they do with it. Politics is in all aspects of how we operate and when I talk about my practice being political it’s just as important to me that I can use abstract forms and thoughts as well as more directly identifiable forms of address. I think it all matters. Refusing to say something has a politics to it, as does elaborating on something explicitly Political. I think about what to address and how to do it – that’s the interesting thing about making art, taking the initiative to make those choices and exhibit thoughts whether they’re fully formed or only half-baked. I like the moment of public encounter, it’s a chance to test things out and learn something about what the work does for other people. And I do that in a very direct way through Workshop by always inviting other people to do things with me.

As for the use of text in my work, I often refer to other artists and writers by quoting them directly, either in the work or through titles. Some of the works in this show are titled using texts by authors whose work I admire and am inspired by - Gertrude Stein, Lydia Davis and Sadie Plant for example. I’m using these texts to open up a conceptual space around the work that may give people another route into my thinking. The Gertrude Stein title for example comes from a text she wrote in 1914 about Roast Beef:

«Any time there is a surface there is a surface and every time there is a suggestion there is a suggestion and every time there is silence there is silence and every time that is languid there is that there then and not oftener, not always, not particular, tender and changing and external and central and surrounded and singular and simple and the same and the surface and the circle and the shine and the succor and the white and the same and the better and the red and the same and the centre and the yellow and the tender and the better, and altogether.»

It’s such a linguistically sensuous and aesthetically evocative bit of writing and when I read it I related it so much to my experience of making art.

Satiate, 2019

Photo: Erik Sæter Jørgensen

AHW: Historically, political activism is closely associated with printmaking. But print as a form of production has had second-class status within the hierarchy of art history. What are your thoughts on this?

CP: A lot of what I find inspiring doesn’t sit high up in the hierarchy of made things - quilts, printed textiles, embroidered samplers, posters, ceramics. I’m interested in how connected these things are to people’s lives through things such as use value, touch, comfort, education and communal activity. And they’re also often interesting to me in terms of how they speak about the history of things women have made. The hierarchy of made things is often based on ideas around quality and exceptionalness, and print by virtue of being reproducible is problematic in terms of its exceptionalness. But I think there’s a certain freedom that comes with working with more peripheral forms – there’s more room to move within them and it’s interesting to connect with histories and legacies that are lesser explored.

* Formerly Justice for Domestic Workers - «The Voice of Domestic Workers is an education and support group calling for justice and rights for Britain's sixteen thousand migrant domestic workers. Our work seeks to end discrimination and protect migrant domestic workers living in the UK by providing or assisting in the provision of education, training, healthcare and legal advice.» www.thevoiceofdomesticworkers.com